Pigs Might Try

Putting a pig on trial appears to defy logic, but in medieval France it gave rural folk the illusion of order in a frightening world.

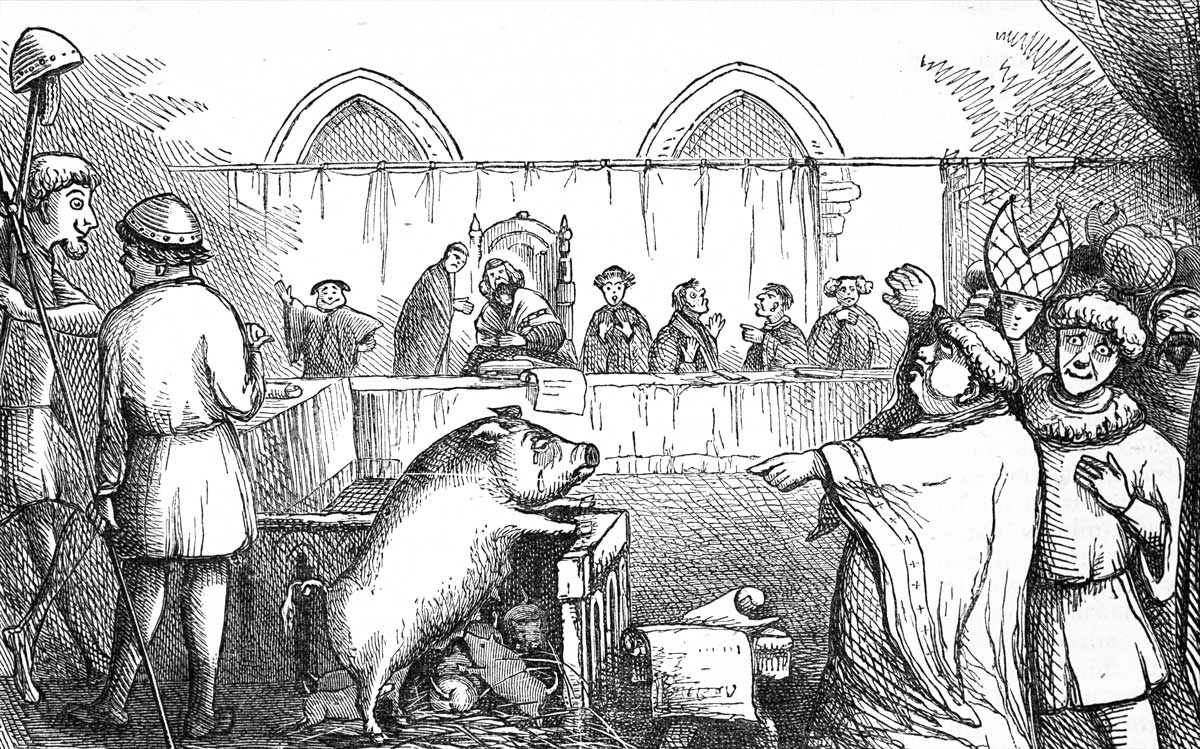

In December 1457 a sow and her six piglets were arrested in Savigny for the ‘murder’ of a five-year-old boy. Together with their owner, Jehan Bailly, they were dragged off to jail; and a month later, they were put on trial before the local judge. According to the court records, three lawyers were present: two for the prosecution; one (perhaps) for the pigs’ defence. Nine witnesses were called by name, in addition to several others whose identities have been lost. Based on their testimony, the judge decided that, while Bailly should have kept a much more careful eye on his animals, responsibility for the boy’s murder lay squarely with the pigs. The sow had clearly been the ringleader. After consulting with experts in local customary law, the judge solemnly sentenced her to death, stipulating that she should be hanged from a tree by her hind legs. The piglets were a different matter, though. Since there was no direct evidence that they had participated in the murder, the judge decided to let them off on the ‘promise’ of good behaviour.

It was a horrifying, surreal episode; but it was far from unique. Animal trials were a remarkably common feature of medieval and early-modern justice, especially in France. Although exact numbers are hard to come by, more than 100 cases are known to have taken place between the tenth and 18th centuries, involving all manner of creatures and crimes. Mules were charged with sodomy, rats and locusts with the destruction of crops, cockerels with laying eggs in ‘defiance of [their] nature’, and dogs with theft. But pigs were by far the most common ‘criminals’; and in almost every case, they were accused of killing a child.

Pigs on trial

The earliest recorded pig trial took place in Fontenay-aux-Roses, just outside Paris, in 1266. By the early 15th century, however, they had become established practice throughout Normandy and the Île-de-France. From there, they spread to Burgundy, Lorraine, Picardy and Champagne, before eventually being exported to Italy, Germany and the Low Countries.

Proceedings generally followed a fixed pattern. Unlike rats, field mice, eels, locusts and ants, which, being ‘wild’, were subject to the jurisdiction of the ecclesiastical courts, pigs – like horses, asses, dogs and sheep – fell under the purview of the secular authorities. After formal charges were drawn up (often using an extremely precise lexicon to describe the alleged offence), their case would be heard by a bailiff or judge, sometimes preceded by a stay in prison. Attorneys would present arguments; evidence would be examined; and witnesses would be summoned. The outcome, however, was rarely in doubt. In most cases, the accused would be found guilty and condemned to death. As in the case of the sow of Savigny, the preferred method of execution was hanging, but other punishments were not unknown. In 1266, for example, the pig in Fontenay-aux-Roses was burnt at the stake; while in 1557, a porcine ‘criminal’ in Saint-Quentin was ‘buried alive’. Responsibility for carrying out the sentence was entrusted to the local executioner. If a town was too small to have its own, one would be summoned from elsewhere. In March 1403, for example, a hangman travelled over 50km from Paris to Meullant to ‘do justice’ to a sow which had killed and eaten an infant; but this was, perhaps exceptional. As part of their remuneration, executioners received a new pair of gloves, as they did after hanging a human, to signify that they accrued no sin in carrying out the sentence.

Reap what you sow

Strictly speaking, of course, pigs should not have been put on trial at all. As contemporary students of the Corpus iuris civilis knew, it was a basic principle of Roman law that animals could not be culpable. Lacking reason, they were incapable of harbouring criminal intent and hence could not be guilty of a crime. As such, any iniuria committed by an animal was the responsibility of its owner or the person to whose care it had been entrusted. If a pig harmed someone because a swineherd could not control it, for example, the swineherd – rather than the animal – would be liable on grounds of negligence. Alternatively, if it was felt that no one could reasonably have prevented the iniuria occurring, the swineherd either had to make reparations or hand over the offending animal to the injured party.

Of course, in the north of France, Roman law had no formal standing in court. Despite the concerted efforts of the Capetian kings to expand the use of royal ordinances, the administration of secular justice was still largely the concern of local seigneurs and was governed predominantly by custom rather than statute. But secular jurists nevertheless regarded the Corpus iuris civilis as a model to be imitated. From the 13th century onwards, they therefore endeavoured to impose order on France’s rather confused legal system by drawing up manuals of local customary law. Known as ‘custumals’, these were often patterned directly after the Corpus iuris civilis – and occasionally even incorporated some of its provisions, including those relating to animal trials. Although not all custumals discussed the practice at length, some of those that did were unambiguous in their condemnation. According to the Coustumes et stilles de Bourgoigne (c.1270-c.1360), an ox or a horse which committed ‘one or more homicides’ should not be put on trial, but merely ‘impounded by the lord in whose jurisdiction they had committed the crime’.

Unfortunately, such ‘academic’ custumals were rarely a mirror of practice. However well-intentioned they may have been, they were often intended to be a guide to how customary law should be – not how it actually was. Especially in regions like Normandy and Burgundy, which jealously guarded their own traditions, it was usually shaped by folk beliefs, which ran counter to the assumptions of Roman law. This was particularly true in the case of animals. Although Christian preachers continued to draw a stark distinction between the animal and human kingdoms, there was a widespread tendency towards anthropomorphism. As Esther Cohen has ably demonstrated, ‘country folk, far from denying animals any human characteristics, consistently attributed to them both reason and will’. This naturally gave rise to the belief that animals could be held responsible for their actions. So-called ‘beast epics’, such as the Roman de Renart, portrayed animals not only with human traits, but actually standing trial – a practice which many local jurists were only too willing to endorse.

But even if pigs could, in principle, be held responsible for their actions, why did communities feel the need to bother prosecuting them at all? Surely it would have been easier (and cheaper) simply to have killed the ‘guilty’ party on the spot, rather than go through the rigmarole of a trial and public execution?

A pig of a puzzle

Even at the time, some jurists were puzzled. Hoping to find an explanation, they tried looking for some purpose to the punishment. Writing in the late 13th century, Philippe de Beaumanoir argued that, since the practice of sentencing a pig to death was legally absurd, its purpose could only be to enrich the seigneurs in whose courts the cases were heard – and that trials were just a glorified fundraising exercise. The only problem with this, of course, was that, since pigs were generally executed, there was nothing left for seigneurs to take for themselves. Indeed, the proceedings actually cost them money. Adopting a rather different approach, Pierre Ayrault argued that the objective was more likely to be deterrence. Although it was true that the sight of a sow swinging from a gibbet was unlikely to stop other pigs from pursuing a life of crime, Aryault thought that it might nevertheless help to convince parents ‘not to leave their children alone’. But this, too, was probably wide of the mark. As some historians have pointed out, if the intention was to deter, why were some animals tried and ‘executed’ in absentia? If there was no pig twisting in the wind, what was there to stir parents to greater vigilance?

In recent decades, scholars have instead sought an answer in the ‘humanisation’ of pigs from accusation through to execution. One of the most interesting suggestions has been put forward by Esther Cohen. Building on trends in legal anthropology, she has observed that, for many rural communities, the ‘murder’ of a child by a pig would have been construed as a grave threat to humanity’s rightful dominion over the natural world. By granting pigs reason, however, it was possible to include them within the purview of human justice – and thereby reassert ‘power over them’. As Cohen has pointed out, in order for this to function effectively, it required not only that pigs be afforded the full benefit of the legal process, but also that they be executed in exactly the same manner as a human being.

Critics, however, might object that, if Cohen is correct in suggesting that the goal was to restore the natural order of things, then there was really no need for a trial at all. Communities could have affirmed their ‘power’ over the animal kingdom just as easily by slitting a pig’s throat – leading us back to the same question we started with.

Perhaps the most convincing explanation is to be found in the role of law itself. As Lesley Bates MacGregor has pointed out, French pig trials were distinguished above all by a ritualistic preoccupation with legal propriety – of which both the punishment and humanisation of the accused formed a part. Everything seems to have depended on the process being handled correctly. The pig was always charged with ‘murdering’ – rather than ‘killing’ – a child; the trial was conducted by the ‘right’ personnel; and executions were carried out according to the strictest demands of haute justice. This was more than just pedantry. According to Paul Schiff Berman, the whole point was to ritually re-impose order on a universe which, after a child’s death, must have seemed frighteningly random and unpredictable. By turning the pig into a ‘human’, putting it on trial and executing it in public, all with the most scrupulous correctness, the world was made stable and comprehensible once again.

Bringing home the bacon

It could never be said that pig trials were edifying. But for legal historians, they really bring home the bacon. By examining how and why they took place, it is possible to gain an unusually clear insight into the development of French justice and the often contradictory influences which shaped its social function. For, while child-killing pigs may have embodied everything communities feared most, their cruel treatment reveals the ambiguities of customary jurisprudence and the difficulties of using (folk) law to impose structure on a harsh and unforgiving world.

Fortunately for pigs, legal attitudes towards animal culpability have changed dramatically since the heyday of porcine procès. Except in the rarest of cases, swine need no longer fear either prosecution or capital punishment. But does that mean that we treat them any more kindly than in the past? Pigs might fly …

Alexander Lee is a fellow in the Centre for the Study of the Renaissance at the University of Warwick. His latest book is Machiavelli: His Life and Times (Picador, 2020).