The War on Dogs

The dog cull of 1760 divided London: were dogs man’s best friend, or plague-ridden pests?

There was outcry in March 2023 when ex-Deputy Health Minister James Bethell revealed that during the early stages of the Covid pandemic, when it was unclear how easily pets could transmit the virus to humans, the UK government considered ‘that we might have to ask the public to exterminate all the cats in Britain’. Three years on, the mere suggestion of a cat cull was met with horror.

Throughout British history, however, widespread culling was a crucial tool in controlling outbreaks of animal diseases and, of course, culling remains standard practice for many livestock diseases. Zoonoses – diseases that are transmittable between animals and humans – have a knack of challenging the relationships between people and their pets.

During the Great Plague of 1665, the Common Council of the City of London decreed ‘that all dogs and cats should be immediately killed’ to stop the spread of the bubonic plague. In his heavily fictionalised account of the epidemic, Daniel Defoe generously estimated that ‘forty thousand dogs, and five times as many cats’ were killed as a result.

Bubonic plague aside, cats were seen to pose far less of a threat to human health than domestic dogs. Few diseases caused such public panic as canine madness or hydrophobia – the condition known today as rabies. Although there were a few remedies that were believed in the 18th century to offer protection from the illness, unless a bite from an infected animal was immediately cauterised the hydrophobic patient faced certain terrifying death marked by extreme changes in their behaviour. Little wonder people went to such lengths to control outbreaks of the disease among local dog populations. But, as pet ownership became increasingly celebrated and society placed higher stock on sentimentality, more and more people – particularly middling-sort urbanites who were dog owners themselves – began to question the necessity and morality of these directives.

Late in the summer of 1760, London was gripped by reports of mad dogs attacking people in the streets. On 26 August the Common Council of the City of London met and the Lord Mayor, Sir Thomas Chitty, issued a proclamation declaring that for the next two months, any dogs in the streets of the city should be killed and buried in mass graves. Similar orders followed in the surrounding areas. Monetary rewards were offered to the officials initially tasked with the culling, but the cull inevitably descended into mob violence. Even pets were caught up in the bloodshed. The cullers clubbed pointers standing on their doorsteps and drowned greyhounds going for walks. A dog leaving the city on a lead was reportedly bludgeoned in the street. The dog-loving writer and antiquarian Horace Walpole described the carnage he saw during the first week of the cull in a letter to a friend:

The streets are the very picture of the murder of the innocents – One drives over nothing but poor dead dogs! The dear, good-natured, honest, sensible creatures! Christ! How can anybody hurt them?

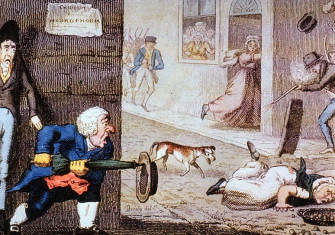

This sort of dog cull was not particularly unusual in itself – Edinburgh saw a cull of street dogs in 1738. Rather, it was notable because it was met with such vocal opposition. An artist produced a satirical print of the cull depicting Thomas Chitty as King Herod and the cullers as violence-hungry thugs. Londoners began writing letters to newspapers criticising the Common Council’s order. Many were concerned that the brutality meted out to dogs might awaken latent savagery that could be transposed onto humans. There was also widespread belief that the outbreak of canine madness had been exaggerated by the newspapers, and the cull an overreaction. For many, however, it was the suffering of London’s dogs that moved them to oppose the killings.

Dog owners were at the forefront of this campaign. One imagined the petition his own gundog, Sancho, might have written, reminding the readers of the London Chronicle that dogs had ‘been their faithful companions in their deepest distress, and remained firm in their friendship to them, when all their human acquaintance had forsaken them’. Opponents of the cull happily expounded upon the moral qualities of doghood – especially loyalty. Another correspondent to the same paper argued that when we kill a dog, ‘we in all probability destroy the only friend who would not desert us in distress’.

Humans often measured up poorly against such high standards. One animal lover complained that London’s dogs were the victims ‘of men more worthless than the animals they destroy’. A letter to the editor of the Public Ledger rejecting the charges levied at London’s dogs asked whether ‘if all useless, mischievous and hurtful creatures were to be destroyed, how many Bipeds, do you think Sir, would escape?’

Such attitudes baffled and horrified proponents of the cull. One correspondent writing to a newspaper in September 1760 criticised dog owners who prided themselves on their love of their animals but were unmoved by the suffering of other people, declaring that ‘the lives of ten thousand Dogs should not be put in competition even with the peace of mind, much less with the life, of one individual person’.

The 1760 cull marked a watershed moment in attitudes towards pets in Britain. It exposed a rift in society between those who saw the dogs of London as walking contagions and those who saw them as potential friends. Wholesale culls soon became a thing of the past and, even though street dogs remained a public health concern into the 19th century, authorities responded by rounding them up and killing them behind closed doors. In turn, these dogs also became objects of popular sentiment and pity. A new breed of dog lover had emerged who would rather face a potential life-threatening risk to their health – and that of other humans – than have innocent dogs die. This world view saw dogs not merely as useful tools, or fellow creatures, but as inherently good beings – and superior to some people.

Stephanie Howard-Smith has a PhD in the cultural history of the lapdog in 18th-century Britain from Queen Mary University of London.