The World’s Local Religion

On the 500th anniversary of the origins of Protestant Christianity, how should we understand its spread – from an academic dispute in a second-rank German university to a global faith that embraces up to a billion people?

If we had been telling the story of the spread of Protestantism on the 450th anniversary of the Reformation, it would have been a tale of missionaries and colonial empires. We would have linked the slow start of the Protestant global mission to the fact that the Protestant powers were imperial latecomers. We would have seen the missionary acceleration in the 18th and 19th centuries as piggybacking on imperialism. And, from the perspective of half a century ago, we would have concluded that this process was probably about to go into retreat and that the missionaries’ Christianity, both Protestant and Catholic, would be shrugged off along with colonial rule.

But it is now clear that the end of the European empires coincided with a dramatic surge in global Protestantism. Close to a third of Africa’s population are now Protestants (broadly defined). In Asia the picture is more varied, but there has been spectacular growth in Korea and in China. Perhaps the most extraordinary developments are in South America, long assumed to be a Catholic continent. According to a detailed 2014 multi-country survey, 19 per cent of Latin Americans are now Protestants, rising to 26 per cent in Brazil and over 40 per cent in much of Central America. More than half of these are converts.

This is not now a simple story of missionaries and empires. The history of Protestantism’s global expansion suggests that missionaries, especially those working closely with empires, have generally not been very successful. The almost total failure of Protestant missions in the 16th and 17th centuries (in contrast to the dramatic successes of their Catholic contemporaries) can be put down largely to the subjection of most Protestant churches to state power, which starved missionary efforts of resources; and to most early missionaries’ assumption that converts needed to be ‘civilised’ as well as Christianised. The missionary effort expanded enormously from the 18th century on, but the direct returns on that effort – in terms of actual converts – were very uneven.

Where Protestantism has succeeded, it has done so by making itself the world’s local religion, adapting promiscuously to whatever situation it finds itself in. The real story of global Protestantism is not about missionaries, but about the people who have made it their own.

*

The 17th-century Dutch colonists at the Cape of Good Hope quickly concluded that the Khoikhoi people could not be converted: as one minister put it, ‘they are so used to running about wild, that they can’t live in subjection to us’. Undaunted, in 1737 a young Moravian missionary named Georg Schmidt established a commune 80 miles east of Cape Town. In 1743 the Dutch church authorities forced him out, but as a parting gift, he left his Dutch New Testament with a Khoikhoi girl whom he had baptised Magdalena.

In 1792, Moravian missionaries were able to return. On their arrival, they were greeted by the now elderly Magdalena, who unwrapped her treasured Bible from its sheepskin case. Her failing eyesight meant she could no longer read herself, but she had a young woman read from it to the newcomers. The community had endured in isolation for half a century, meeting under the pear tree Schmidt had planted, teaching their children to read Dutch. The visitors’ appearance did not surprise them. God had told them in dreams to expect their return soon.

No doubt that story has grown in the telling. But it is an early sign of how Africans could make Protestantism their own. The Protestant missionaries who surged into southern Africa expected to found and then control churches, but their grasp could not equal their message’s reach. When one early missionary toured the Xhosa of the eastern Cape in 1800-1, his mission bore no apparent fruit at all. It was nearly 15 years later that Ntsikana, a highborn Xhosa singer who had heard one of the sermons, experienced a conversion. Following a vision, he was inspired to begin chanting early versions of what would become the first Xhosa-language Christian hymns. He set himself against a millenarian Xhosa prophet, who was attempting to mobilise his people for war against the encroaching Europeans. Ntsikana accused him of mendacious self-aggrandisement and preached repentance and reconciliation instead, attracting a substantial multi-ethnic following.

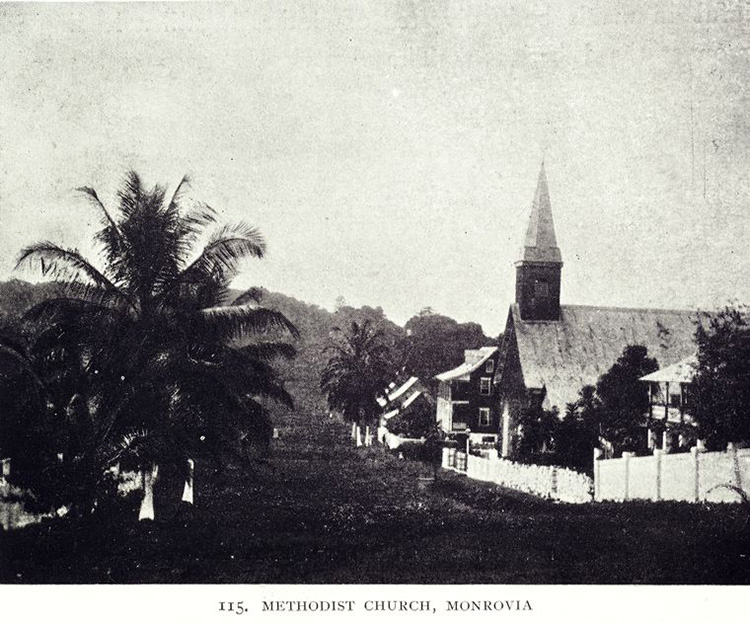

Even in areas under full imperial control, Protestant converts began to peel away from mission churches to set up independent outfits of their own. The Thembu Church, founded by an ex-Methodist in 1884, argued that if Queen Victoria could be head of the Church of England, the Thembu paramount chief should have the same rights in his lands. It was the first of a wave of African ‘Independent’ churches, led by African Protestants frustrated by being systematically sidelined in mission churches. They were slow to form and much slower to win recognition from establishment Protestant churches. But those independent churches have been the most powerful engines of African Christianity’s modern growth.

Most of those African independent churches can be broadly classified as ‘Pentecostal’, as can the churches dominating Latin America’s new Protestant landscape. Such communities may not always speak in tongues, but they certainly practise prophecy, ecstatic worship, miraculous healing and exorcism.

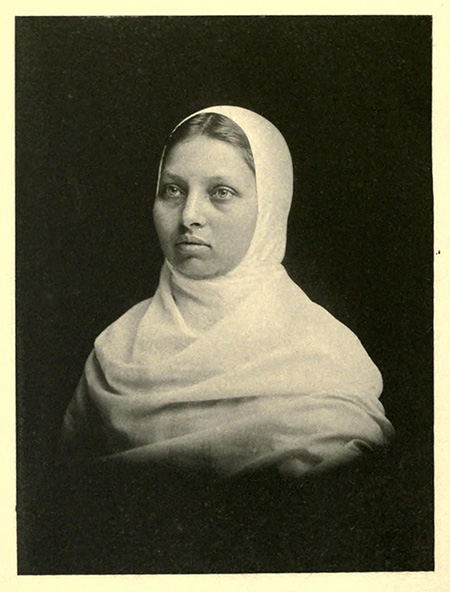

Pentecostalism itself has a missionary mythology, which traces its roots back to Los Angeles in 1906. But its roots are much deeper and more global than that. Revivalist, ecstatic piety runs through Protestantism’s history like an ore vein: by the early 20th century it was emerging all over the world. Pandita Sarasvati Ramabai, a Protestant campaigner for women’s rights in her native India, had an experience of ‘the personal presence of the Holy Spirit in me’ in 1894. Stirred by reports of the great Welsh revival of 1904-5, she organised prayer meetings in the women’s refuge she ran, sparking a months-long revival marked by long prayer meetings, miraculous healings, speaking in tongues, over a thousand baptisms and around 700 female missionaries venturing into the surrounding communities. It was accounts of Ramabai’s revival, rather than anything coming from Los Angeles, that sparked the first Pentecostal movement in Chile shortly afterwards.

Ramabai’s movement also helped to inspire the wave of revivals which swept Korea in 1907. One longstanding missionary in Korea wrote that those revivals had brought him, too, to a kind of conversion:

Until this year I was more or less bound by that contemptible notion that the East is East and West, West ... I had said the Korean would never have a religious experience such as the West has. These revivals have taught me [that] the East not only has many things, but profound things, to teach the West, and until we learn these things we will not know the full-orbed Gospel of Christ.

Missionaries in Korea rapidly relinquished control of their churches. The last non-Korean moderator of the country’s Presbyterian church stepped down in 1919. The astonishing growth of South Korean Protestantism after the Second World War has many causes, not least Christianity’s part in opposing both Japanese imperialism and North Korean Communism. But it would have been impossible without the genuine indigenisation of the Korean churches.

*

No country was the focus of more missionary effort in the imperial age than China. Yet the results were underwhelming. By 1949 Chinese Christianity was highly visible, especially in the cities, but its numbers did not match its status. For many of its high-profile Chinese converts – such as the Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek, baptised as a Protestant in 1930 – it was more a political tool than a personal faith. It was also widely loathed as a foreign religion, a symbol of China’s humiliation by the western powers. After the Communist revolution in 1949, the Party, keen to wean its people off this imported opium, expelled all missionaries and progressively squeezed the churches. At the outbreak of the Cultural Revolution in 1966, all religious practice of any kind was banned.

Perversely, this was the foundation of Chinese Protestantism’s astonishing modern growth. Protestant numbers are guessed to have increased five- or six-fold during the Cultural Revolution, when the clandestine meetings often called ‘house churches’, the main engine of Protestant growth in modern China, first formed. They did so, not in mission Christianity’s urban strongholds, but in rural areas. With missionaries expelled, China’s Christians were no longer tainted by association with them and the indigenous, ‘independent’ churches that had already been formed could take the field. The Cultural Revolution’s scorched-earth policy towards all old customs, beliefs and habits provided an opportunity for invasive species to take root. In that environment, Protestantism had a unique advantage: weightlessness. Unlike all of its religious rivals, it had no material requirements, cost no money, needed no professionals and left no evidence. Even if there were no Bibles, Protestants only needed prayers and songs and faith and the name Jesus.

So the partial legalisation of Protestant practice in China from 1979 onwards led to a rising wave of conversions that has scarcely eased up since. There are – probably – not yet 100 million Christians in China, but unless trends change sharply there will be soon. Chinese Protestantism is in a sweet spot: persecuted enough to keep it nimble and honest, but not enough to threaten its existence. An important part of its success is that – as hostile observers often agree – it has managed to win a social reputation for moral rectitude, in fostering everything from family reconciliation to honesty in business. Christians in many ages have aspired to such a reputation. Few have succeeded.

*

Since the European Reformation is often associated with political upheaval and notions of liberation, we might ask what the effects of this new global Protestant Reformation might be. There have been some excitable suggestions that it will be a Trojan horse for western or American values worldwide. But this latest version of missionary Protestantism will be no more successful than its predecessors.

If there is one feature all these global Protestantisms have in common, it is their withdrawal from politics. Indigenous Protestant churches under politically repressive regimes of all kinds – from the military dictatorships of South Korea and Latin America, to the Communist regime in China and the apartheid state in South Africa – have deliberately and self-consciously refused to protest against their rulers, even as churches founded by missionaries have sometimes made heroic stands against them. Such churches have often been accused of being dictators’ friends, which in some cases is plainly true, but the truth is more subversive. They are generally not interested in politics at all, beyond the simple, non-negotiable demand to be able to meet and worship as they see fit. Where they have mobilised politically, it has been in response to ideologies which seem to threaten that demand: Marxism in Latin America, Islamism in Nigeria. Otherwise, their working assumption tends to be that politics is distant, corrupt and unimportant. They are often remarkably female-dominated, in societies which assume that women belong to the private sphere. They look for salvation not to their governments but to God.

Our age has produced two rapidly expanding global religious movements. One of them, jihadist or revolutionary Islam, has thrust itself onto the world’s notice, since it is explicitly political in its ambitions. The other, renewalist Protestantism, has attracted much less attention, since its focus has been on the lives of individual believers and of communities. How long it can maintain its political blind spot remains unclear. In parts of Africa and Latin America, Protestant churches are being drawn into politics, not least by those who want their votes. But the secret of this Reformation’s success is that it remains a local religion, not only in its variety but also in the sense that it is focused on localities, communities and individuals – even as it quietly turns itself into the local religion of the world.

Alec Ryrie is Professor of Theology and Religion at the University of Durham. He is the author of Protestants: The Radicals Who Made the Modern World (Harper Collins, 2017).